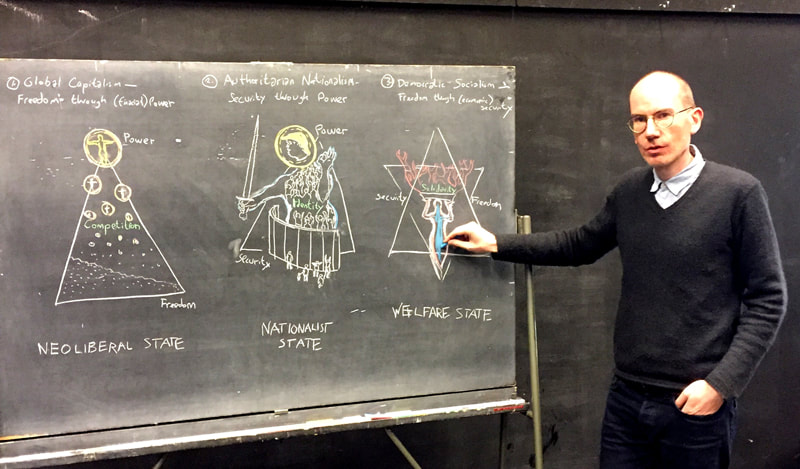

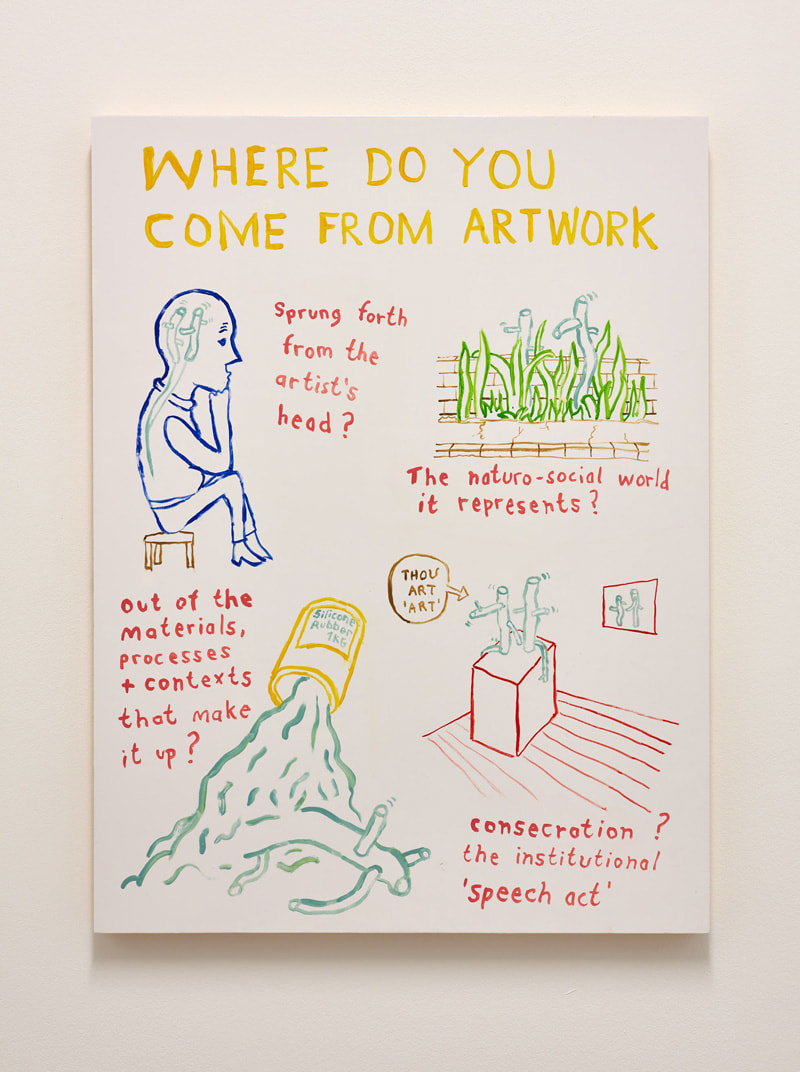

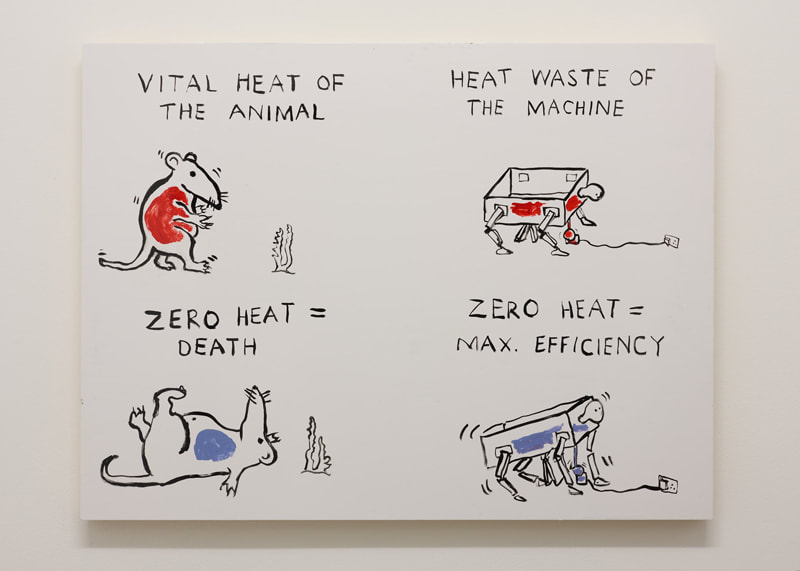

I see diagramming as a real-time form of thinking rather than a map of pre-existent thoughts. It’s a manual and graphic mode of figuring out, testing how things connect. The diagramming process makes abstract or non-visible forms and forces visible and available for further mental and manual manipulation in a sort of relay. My use of this way of working has probably evolved from my own mental limitations, my need to transcribe or inscribe concepts and arguments into a set of relations made visible on the page in order to get a grasp of what’s being said. This is especially the case with philosophical texts, where understanding can be facilitated through the diagramming process. I’ve always been someone who has scribbled in the margins of books. Diagrammatic artworks stem from these initial ad hoc processes. For example, live-drawing versions of Metallurgy of the Subject, or Diagramming Politics emphasise the temporal dimension of thinking-through or actualising a problem in a public setting. They allow for commentary to accompany drawing as well as two-way communication with an audience.

With diagrams, the aspect of moving around the object of thought is crucial. The conventional diagram’s flat plane, and its reduction of this mental object to a set of relations that matter, presents a synoptic all-there-at-once view, which can be utilised to test ideas and possibilities about and for the object in an iterative process of trial and discovery. One of the most basic and familiar diagrammatic forms is the timeline, which allows us to freeze what is always slipping away and dragging us along, namely time. We are invited to move back and forth in time, spot patterns that we hadn’t suspected, focus on moments of a process, add events along the way, and so on. Through this spatialisation, a temporal process or operation can become an object to be contemplated and worked over in our own time. As an educational tool, animation can greatly increase the capacity diagrams have to explain processes, although the technical efforts of animating a diagram (and the apparatus needed to play it) can detract somewhat from the pragmatic and modest immediacy of thinking as real-time diagramming, and the way a diagram can invite graphic alteration. There is a danger in all this, of course, the danger of representation in general, that the model is taken for reality. For example, that we begin to imagine that time really is like a linear graph (suggesting that time travel is possible), or that the conventional diagram of an atom really resembles an atom, rather than being a highly schematic convention. But I’m less interested in diagrams as a pre-established or final, text-book representation, and am more focussed on diagramming as an activity of manual manipulation – an embodied, gestural and subjective grappling with a problem, or articulation of a question.

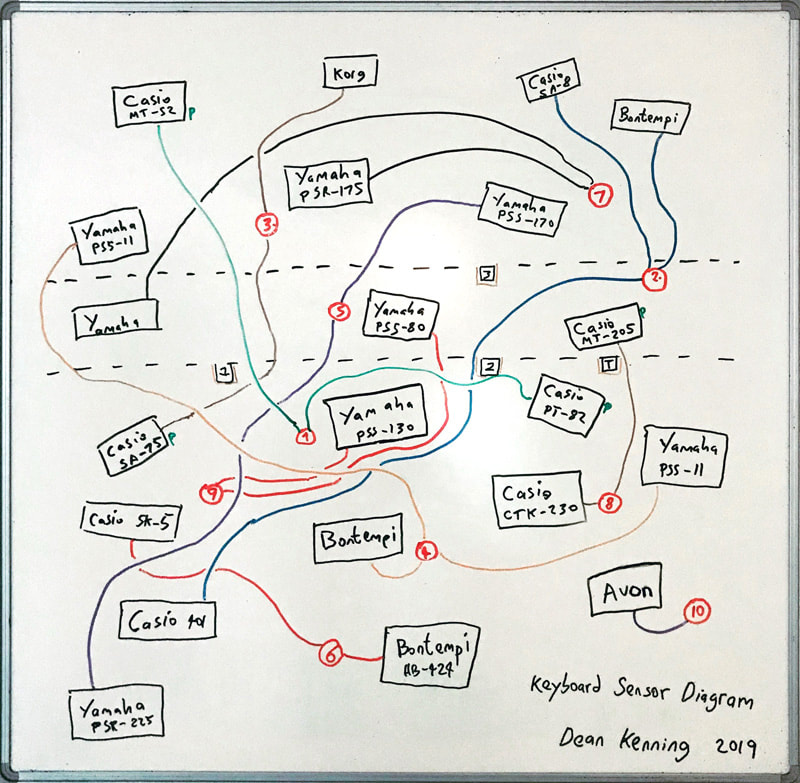

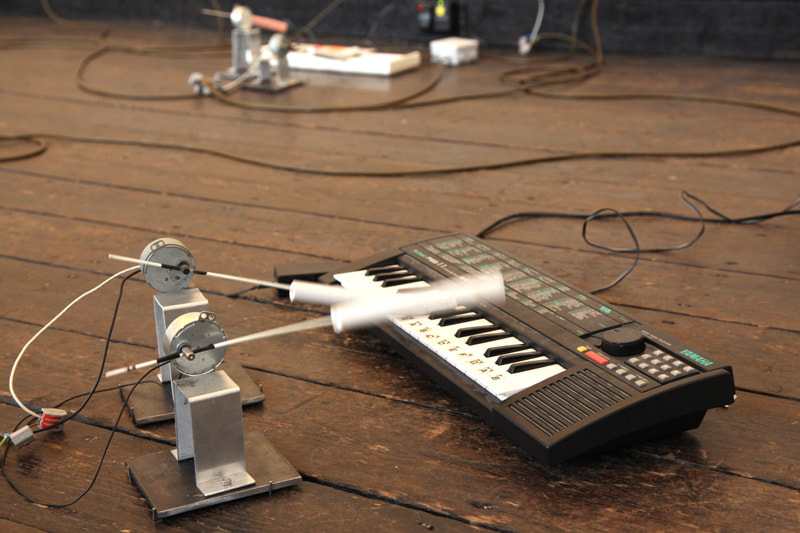

A large part of my practice is sculptural or spatial, and this can extend to diagrams. In three dimensions you lose the synoptic overview which is so promising for logical inference, pattern spotting and extension through graphic manipulation. I do, however, now view my more recent kinetic works as diagrammatic, the sensor-based and robotic works that activate a physical space in unpredictable ways. The Origin of Life is a kinetic sound work consisting of twenty-two synth keyboards played by motorised rubber ‘fingers’ which are set into action through the movement of visitors in a space. I have a diagram schematic of all the connecting wires, how they join motion sensors with motors throughout the gallery space. This is a practical overview of a complex relation between parts, something I constructed, referred to and altered in the process of assembling the physical installation. However, it also becomes the diagram of all the, potentially infinite, combinations of kinetic action, which are the trigger for various sounds and combinations of sound. Conversely, the aesthetic and sonic affect experienced by a visitor when encountering the installation, becomes a sort of sensual and subliminal diagram of the points of electrical connection, communication and audience position at any moment. This notion of the diagram is less about representation in any obvious sense, and more about emergence – the way points of variable physical connection enable a very wide range of possibilities when actions are not pre-programmed or mapped out like a conventional score.

I don’t aim for the universal in diagrams, but the singularity of each diagram. With the Social Body Mind Mapping workshops (which I have done regularly with art students), the ‘subject’ of the map or diagram is an existing artwork made by each participant which they draw an image of on the page. The participant’s artwork then goes through a process of ‘estrangement’ by means of a schema consisting of four categories – capacities, motivations, resources and organisations – under which various terms can be listed. The categories are common but they act as a modulating device to distance the artwork under consideration from the participant’s immediate thoughts about it. At that stage each participant’s actual diagram can be formed as a singular way of thinking-through their artwork, connecting determining social aspects with seemingly more personal motivations, ideas, interests, etc. It is both a way of ‘remembering’ or ‘recognising’ something about the work that may have been lost in its realisation and interpretation, and a way to unlock new ideas and meanings. The final stage is to share those thoughts and connections with the group, because, for me, a diagram is always an invitation for discourse leading to possible modification, rather than something fixed for all time.

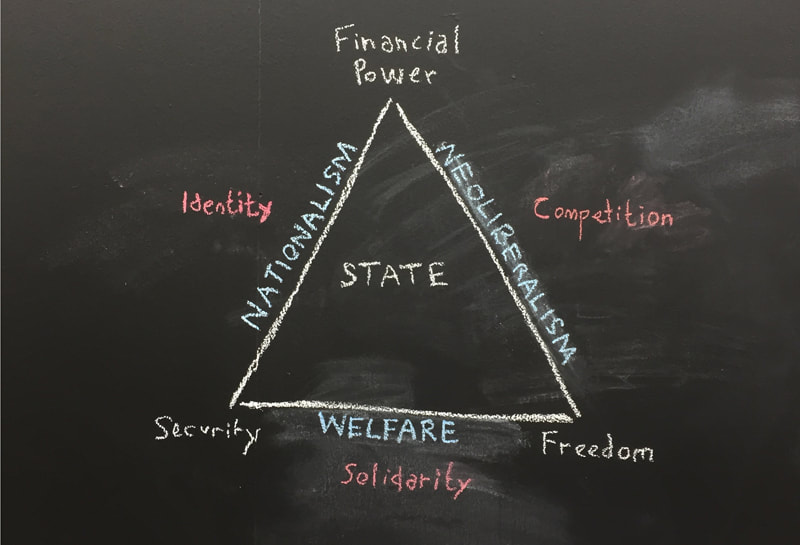

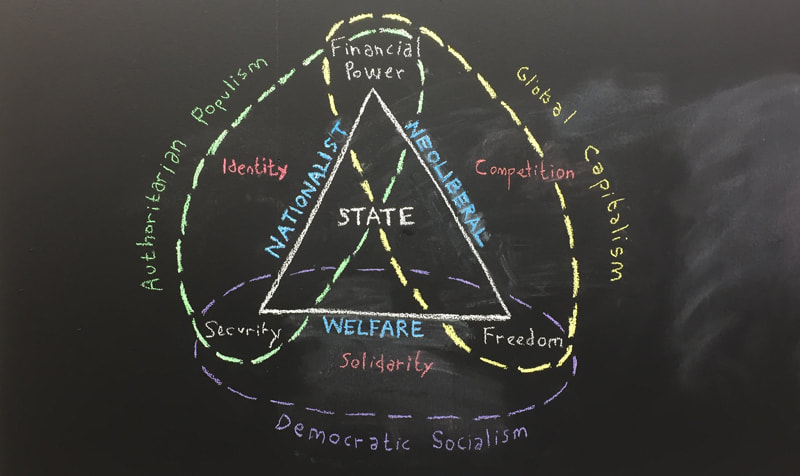

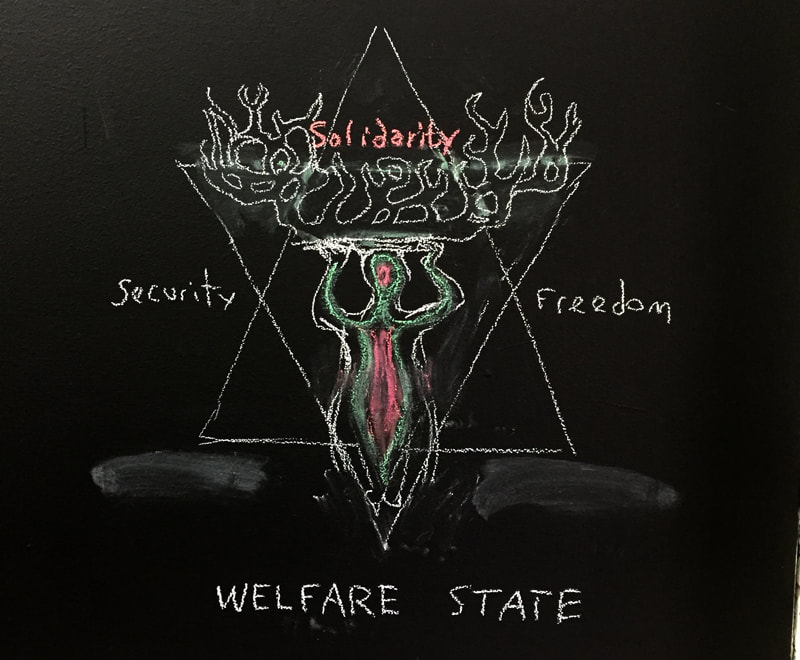

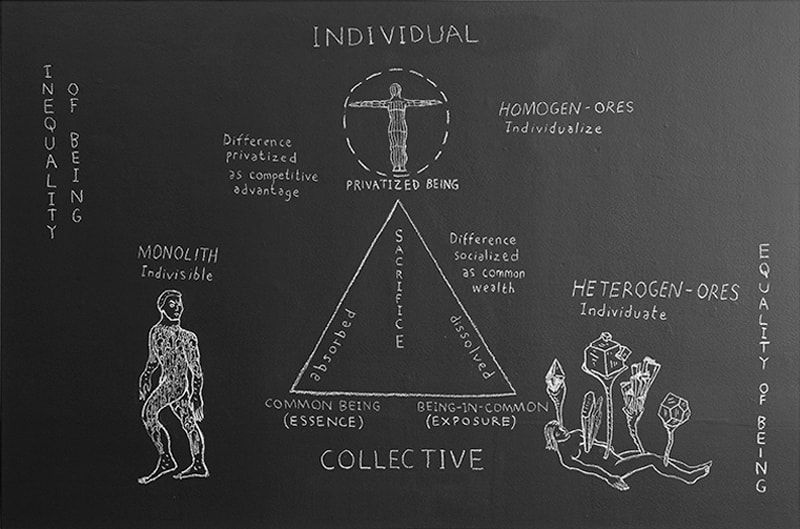

I wouldn’t think of my diagrammatic work in terms of a totalising image, but I am interested in formulating a set of relations which can operate at a general level to encompass specific instances. In Diagramming Politics I construct a sequentially expanding map of politics, taking in what I consider the dominant and available contemporary forms the state takes: neoliberal, welfare state and nationalist (none of which are mutually exclusive in terms of actual states). These positions form logically as the sides of a triangle or pyramid whose points of aspiration or desire are freedom, security and power: neoliberalism operating between power and freedom, nationalism between power and security, and the welfare state between security and freedom. I can then define the principle which defines these ideological positions: competition, national identity and solidarity. This is general, but it can be a way to speak about particular, real world dynamics whilst escaping the pedestrian immediacy by which mainstream political debate has us trapped. How, for example, all three aspirations are addressed in ways which means that politics is often a mix of ideologies with one mode nevertheless remaining dominant, framing the discourse around e.g. ‘freedom’ in particular ways. Rather than being a totalising view, this is more like a moment of pause, a way to engage and grapple with and get a more expansive understanding of politics. It is a generative device which I have used in situations of conversation. Hopefully the diagram forms a map which makes sense and is useful to others, whilst retaining a degree of subjectivity.

I think something like a ‘diagrammatic imagination’ exists within humans, something close to analogical thinking, the way that a set of relations between the parts that constitute one thing gives us a clue to how something else, perhaps something less well understood or completely mysterious, might function as a set of similarly related parts. Combine this iconic and pattern-forming capacity of the imagination with the way that manual mark-making amplifies and extends cognitive capacity and you have in the diagram a fundamental human facility.

The logical positivist Otto Neurath initiated the Isotype pictographic system as a universal language for communicating information. Whilst I admire Neurath’s socialist and pedagogical intentions I am wary of his approach to diagrams which I see as partly responsible for the overload of data visualisation which exists in our contemporary world. For me data, particularly quantitative data, will ultimately always render us passive consumers of information. Active diagramming, by contrast, can at least give us back some agency as we get a chance to formulate connections and relations in our own way, according to the problems that present themselves in various combinations to each of us in specific ways.

C.S. Peirce, the founder of semiotics and great diagram practitioner, viewed the diagram as the principle form of logical reasoning. He defined the diagram as an icon, that is a sign which represents its object by means of resemblance, and resembles it specifically in terms of how the parts making up the object relate to each other. According to this definition you can see how any creative activity, such as mathematics, dance or music could, at least potentially, involve (or be recognised as involving) diagrammatic modes of representation. Diagrams are not limited to graphic figures on a two-dimensional plane; and conversely, a simple hand drawn diagram can be full of subjective or aesthetic intensity, or contain allegorical figures that lead one beyond the object in hand. At the limit of diagrammatic thinking, the philosopher Gilles Deleuze has elaborated a non-representational theory of the diagram, something like a hidden agent or intensive process leading to creative emergence or disruption – this is something I’m currently exploring in a piece of writing for a book on diagrams.

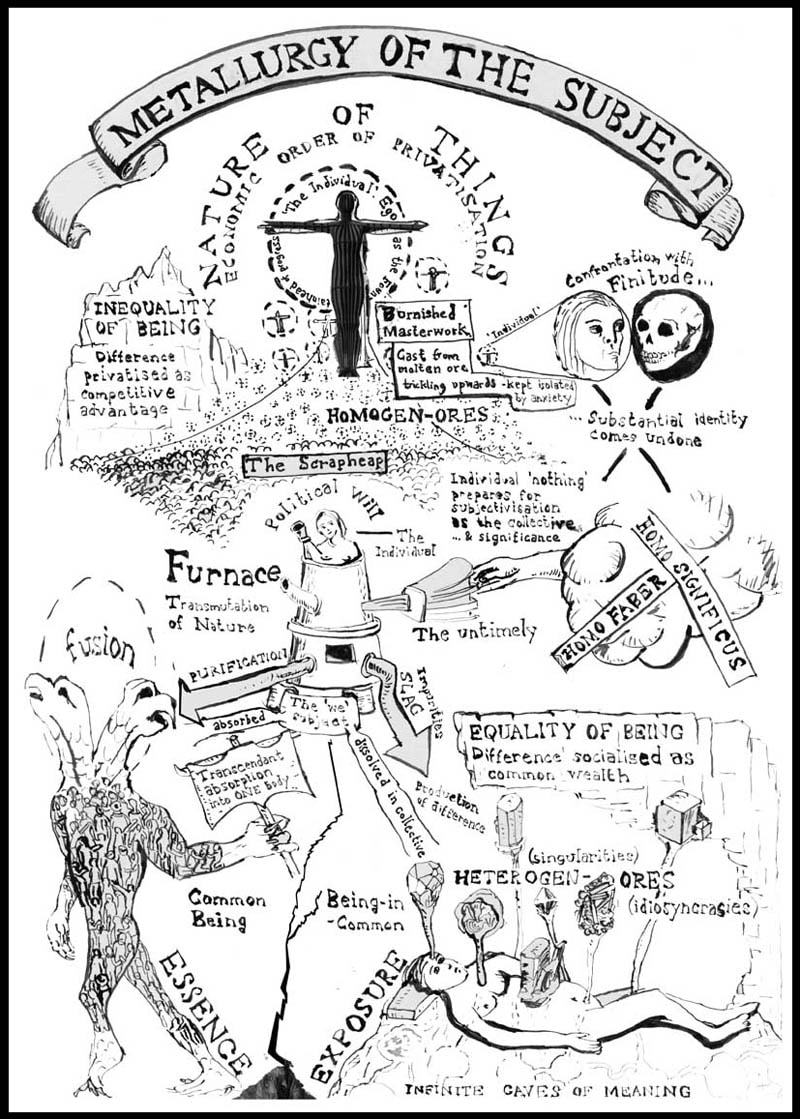

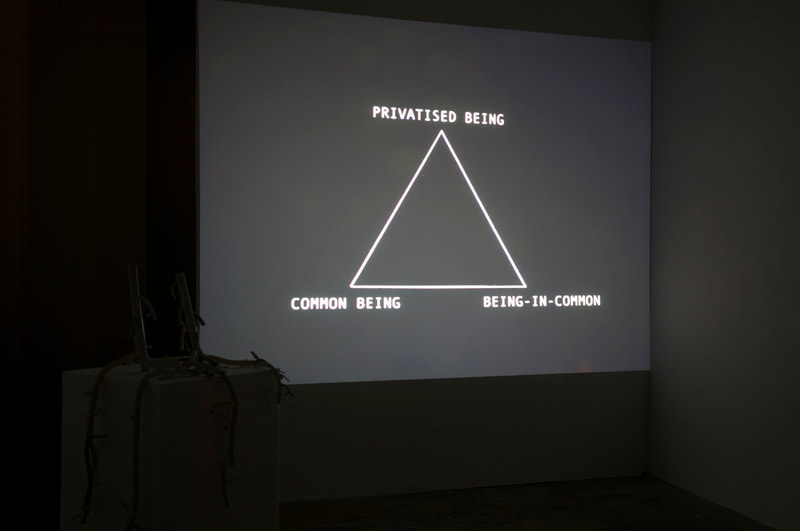

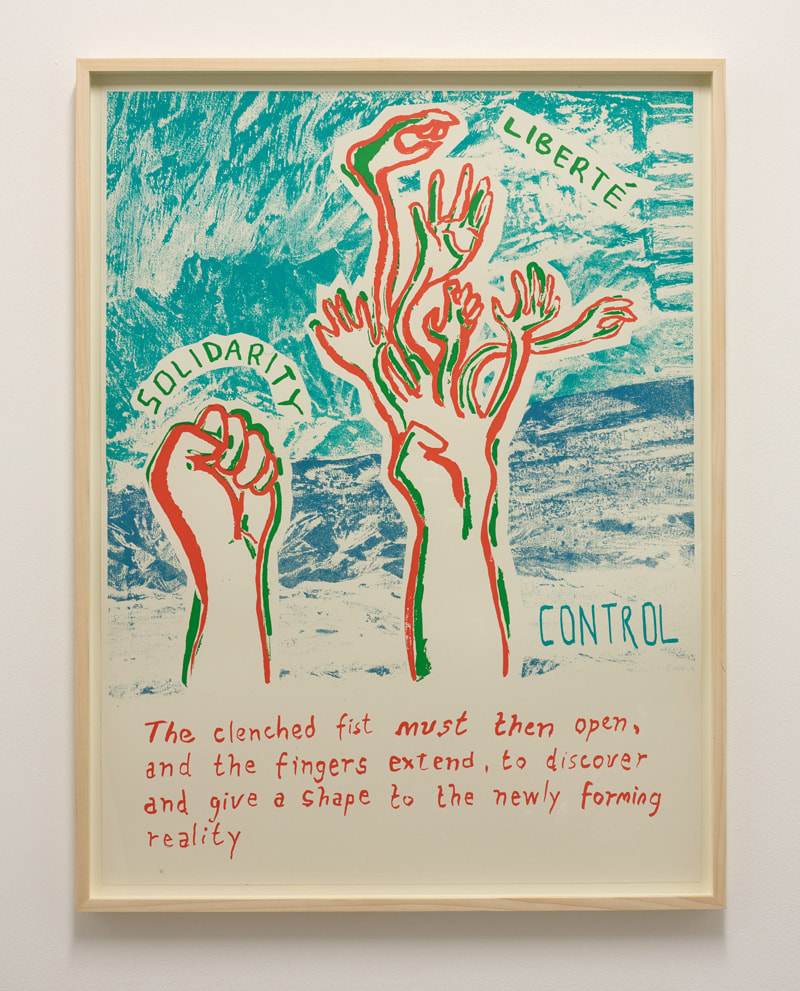

A diagram hopefully illuminates something, but it begins in a state of darkness, of not-knowing. It is like a cave full of colliding figures, ideas and concepts which seem to want to connect. Metallurgy of the Subject was the first consciously diagrammatic work I made, emerging initially at the time when I was writing an academic paper about political philosophy and theories of community. I was reading philosophers like Giorgio Agamben and Jean Luc-Nancy and coming to grips with concepts like ‘being-in-common’ as a positive conception of commonality opposed to free market individualism but escaping the dangers of closed, identitarian or fascist communities. At the same time, I was asked to participate in an exhibition on the theme of the esoteric and occult. I am fascinated by the enigmatic, allegorical images used in Renaissance-era alchemy, this combination of the diagrammatic and the emblematic, of allegorical figures and mysterious, coded text. So Metallurgy emerged from the fusion of contemporary philosophical debates around community with the allegorical imagery of alchemy. The individual transmutes into the collective in one of two ways, just as lead transmutes into gold, etc. Within that diagram, a dark cave plays an allegorical role as a portal of escape. The diagram was like a channel or gateway through which these external ideas and images could be synthesised in a dynamic way. I then utilised this image as a live drawing event where I would talk about what was going on as I was doing it. This was initially in the context of education teach-ins during the protests against the trebling of UK university fees. It took a couple of other forms too, changing in various ways at each point: a more schematic, more bare-boned diagrammatic image; and an animated version with a voice over and soundtrack by English Heretic. I see this project as collective, both in the sense that I was explicitly bringing in concepts and imagery that were external, and in the sense that I used it in quite social situations.

The cave metaphor has also played a particular role in my workshop based diagramming exercises. One thing I do in educational settings is to use diagraming as a mode of close reading of theoretical and philosophical texts. And the text I’ve done most often with students is Plato’s ‘Allegory of the Cave’ from The Republic. Plato’s famous simile of prisoners in a cave is an implicit diagram, as it sets out a hierarchy of relations represented in terms of high and low, light and dark. It is meant to be a universal diagram representing what is ultimately true and what is false. What I have initiated over the years is the production of a large number, over one hundred versions of Plato’s ‘cave’, as students seek to interpret and understand Plato’s text by making their own drawings of it. Sometimes, on winter evening sessions at the Institute of Education, the group all draw their individual caves within a series of interlinking cavity-like forms which I have pre-drawn on the wall. I then turn off the lights so we are plunged into darkness and we travel through each ‘cave’ one-by-one with the use of a torch. Its quite elemental, that being together and talking together in the dark. I call the workshop Plato’s Caves, with an ‘s’ on the end, because, after all, there isn’t one single cave or one single truth, or one single diagram, as Plato thought, but an ever multiplying number of singular caves which connect and resonate through a common purpose.

As with all my work, the diagrammatic work evolves, like a process I’m not totally in control of, but which is affected both by external pressures and happy accidents along the way. I tend to work towards short term specific deadlines rather than having a five-year plan or something, but there is, hopefully, evolution as I draw on and extend upon what has gone before. It is an iterative process with plenty of cobbling and meandering. Then there are moments when I can step back and reflect, or when I am forced by other pressures to reflect on the direction of things, and the relations between different works. It was only after making Metallurgy of the Subject that ‘the diagrammatic’ became a conscious artistic concern, largely in connection with what other people I knew or came to know were doing in a similar area. I then brought this in to teaching practice, which fed back into artworks. The pyramidal form of the Metallurgy diagram generated Drawing Politics, and an engagement with diagram theory has led to new works, as well as the realisation that a very old work, the very first work I made after leaving art college, was a diagram – Reality as a Readymade (co-produced with Bettina Eberhard), which is actually concerned with time travel. I associate diagrams with philosophy - different philosophies have different diagrams. The more dialectical and structuralist approach I initially adopted has probably evolved into something more vitalist and emergent. But most important is the sense of an ethic, which I hope is embodied in diagramming as a question of agency and a process of thinking beyond the self, utilising a visual form which is both democratic and trans-disciplinary.

One of the dangers of diagrams is that what appears to be expansive can end up being restrictive. Attaining a schematic overview, beyond all the random and contingent accidents of existence, whilst a factor in the diagram’s utility, is also a rationalist dream. This rationalism may also seem close to a paranoid or conspiratorial mode of thought which finds connections in random incidents, or joins ever more dots to form a picture which is, paradoxically perhaps, a simplified reality. I’m drawn to the economy of a schema which, by removing all the distractions and linking things up, acts like those truth-revealing sunglasses in the film They Live. But total clarity is a fantasy. The merely additive form of expansive diagram-making is not so interesting to me, that mode of diagramming which merely pulls together lots of different facts in some huge map of connections. At a modest level, mind-maps function that way (with the self often at the centre). This additive diagram of connections is one of the dominant modes of the diagrammatic in contemporary art, but it leaves me cold. I’m interested in something more immanent, self-generating and embodied. I like having fun with diagrams too, revealing something about the operation of diagram types through humour, as with my Pop Diagrams: Craig David’s Week Pie Chart, or the Jackson Five Flowchart. I suppose I want to avoid both dangers: the self-obsession of the paranoid, caught at the centre of their map of power; and the objective, dispassionate or sociological bird’s-eye view of truth. There are lines that one follows, and links one makes, but these are always singular and mysterious in their origin and their powers of compulsion. What’s important is where the lines take you.

Art can be political in different ways: in its subject matter, its immediate usage, its mode of production and distribution, etc. Some of my diagrams take politics as their subject, and are coming out of a commitment to socialism-communism, as well as investigating what concepts like socialism or communism mean in terms of political critique and modes of being. Diagramming in my practice often arises practically out of group situations, whether that is in teaching or through art groups I’ve been part of, such as the Capital Drawing Group project or DRG (Diagram Research Group). Works like Drawing Politics and Metallurgy of the Subject make use of visual emblems, which I see as very different from Isotype-style pictograms in that they don’t seek to simplify things but to deepen and darken them through the use of both analogy and allegory. These emblems operate as a third dimension on the picture plane. I’ve used some of those politically oriented diagrams in more actively political situations. But most of all I see the politics of diagrams in their democratic and practical character. Diagrams are a common form of visual practice which have a modesty in terms of their ad hoc usage. I want my diagrams to inspire other people to make their own diagrams. They are not objects to be merely consumed, either as special aesthetic objects (‘art’) or as information. Diagrams as thought processes can be relays for the production of new diagrams rather than visual arrays of information to be responded to in a cybernetic process of self-optimisation, like the majority of diagrams and visual data generation that exist today. The real politics of diagrams for me lies in their promise of a degree of agency, of figuring stuff out through an act of drawing rather than merely observing and accepting what’s served up and the order in which it is served up.

I like to think my diagrams have a degree of autonomy outside of either the art system or the academic system, even though I am operating within both. Through diagrams, I am hoping to avoid both the aesthetic immediacy of ‘white cube’ art objects, and the sorts of academic expertise and objectivity that can suck the life out of an art practice. My diagrams can be shown or utilised in different settings, such as galleries or academic situations, without being overly determined by those contexts – at least I hope this is the case. I wouldn’t make any strong claims of radicalism and would focus more on pragmatism and diagrams as a common form of visual culture which is a way in for people without having to have a university level art education or a knowledge of contemporary art. I hope that my diagrams invite the viewer in and make them active as a reader and interpreter of the image.

I hope my diagrams invite commentary, verbal communication and response. There are aesthetic aspects but I don’t expect the work to be self-contained, but rather to spill over into discourse. Hopefully there’s more of a sense of things colliding and manual thinking, a more physical, contingent and messy working through of something, rather than a final form, aesthetically or conceptually sealed. As I’ve said, I often talk through the diagrams, sometimes in the process of a live drawing. Seeing the way a diagram is formed in stages, understanding that evolution of form and ideas, can give a deeper understanding than seeing the diagram only in its completed state. There is a sense of how things could go off in different directions at each stage.

My whole interest and motivation with respect to diagrams is to overcome the sorts of dualisms that separate things off from each other in distinct categories: mind-body, individual-society, cognitive-creative, writing-drawing, reflection-production, philosophy-art. In fact, everything connects and new phenomena emerge as a result of relations and reactions amongst things, across physical, psychological, cultural, species etc. levels of reality. Everything exists on the same plane of reality – this is a view that both Peirce and Deleuze subscribe to, despite the differences in their philosophies. The boundaries we rely on to identify things as individual are permeable, whilst what constitutes each individual thing turns out to be a coalition of multiple other things with their own permeable boundaries. Our brain is plugged into aspects of the world through real-time modulating sensory-nervous and hormonal systems, but it is also filled with conventional attitudes and habit-forming beliefs via human-made symbols and behavioural or gestural signals, which other stimuli may disrupt or transform. We ingest the ‘outside’ world and filter the truth of it through various possible frames. In my diagram Making Sense, there is a flow of sensory and nervous energy, extending outwards into the world before being drawn back up into the psychic or mental apparatus in a feedback loop – which can be viewed both as a homeostatic engine maintaining balance, or as a ‘stuck machine’ unable to adjust its own filter settings.

Sometimes when I’m drawing a diagram, working something out graphically, that link with the formation of neuronal connections can seem like more than an analogy, as if, with the gestural inscription on the page, something is being inscribed on the brain itself – new synaptic relations are forming literally as connections are being made on the page.

Sometimes when I’m drawing a diagram, working something out graphically, that link with the formation of neuronal connections can seem like more than an analogy, as if, with the gestural inscription on the page, something is being inscribed on the brain itself – new synaptic relations are forming literally as connections are being made on the page.

You ‘read’ a diagram following its path which is often indicated by arrows. In terms of production, it leads you somewhere, and it often performs a logical operation which means there is a temporal dimension. A transformation occurs. In Metallurgy, for example, the ‘individual’ subject transforms into the ‘collective’ subject in one of two ways. In Making Sense there is an endless feedback loop of sign-response moving up through the body then out and down to the environmental context, the way a tube map or an electrical circuit diagram may represent the directional flow of passengers or electrons. The point where the diagram comes to rest as an image to be shared is both a goal to aim for, but also it might be seen as a resting point, a stage in a continuing process. Fundamentally I see diagramming as an iterative and plastic process. It is a moving, changing line rather than a representation of some foundational truth. Routes not roots, as Paul Gilroy says.